When a new drug hits the market, it doesn’t just appear out of nowhere. Behind every pill, injection, or inhaler is a decade of research, billions of dollars spent, and a legal shield called a patent. But patents don’t just protect companies-they also set the stage for cheaper, life-saving generics to enter the market. This tension between innovation and access is the core of modern pharmaceutical law.

How Patents Work in Drug Development

A pharmaceutical patent gives a company exclusive rights to make, sell, and distribute a new drug for 20 years from the date it’s filed. But here’s the catch: that 20-year clock starts ticking long before the drug reaches patients. The average drug takes 10 to 12 years just to get approved by the FDA. That means the actual time a company can sell the drug without competition is often only 8 to 12 years.

Developing a new drug costs about $2.6 billion on average, according to Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development. That money pays for labs, clinical trials, regulatory filings, and failed attempts. Without patent protection, any competitor could copy the drug the moment it’s approved-and the original developer would never recoup their investment. Patents exist to make that risk worth taking.

The Hatch-Waxman Act: The Balancing Act

In 1984, Congress passed the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act-better known as the Hatch-Waxman Act. Named after its sponsors, Senator Orrin Hatch and Representative Henry Waxman, this law created a system that lets generic drug makers enter the market without waiting for every patent to expire.

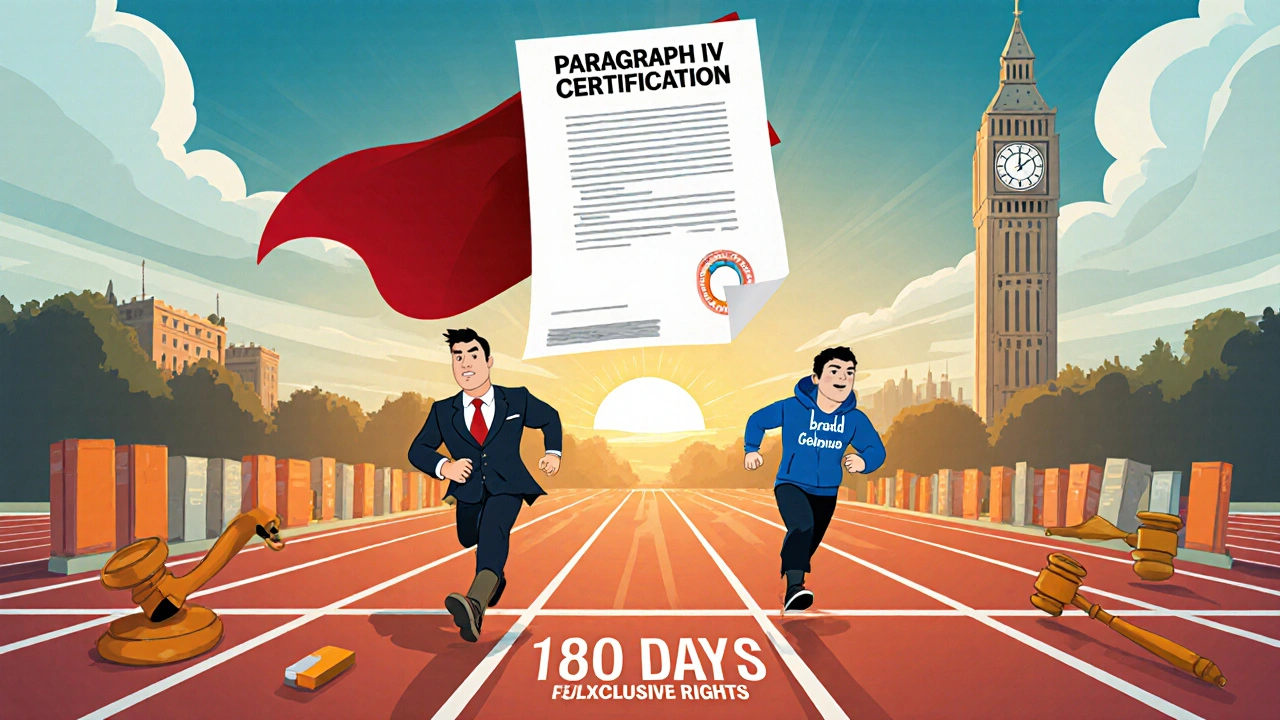

Before Hatch-Waxman, brand-name companies could block generics simply by filing lawsuits. The new law changed that. It allowed generic manufacturers to file an application with the FDA before a patent expired, as long as they certified that the patent was invalid, unenforceable, or wouldn’t be infringed. This is called a Paragraph IV certification.

When a generic company files a Paragraph IV challenge, the brand-name company has 45 days to sue for patent infringement. If they do, the FDA is automatically blocked from approving the generic for 30 months-no matter whether the patent is actually valid. This gives innovators a guaranteed buffer, even if the lawsuit is weak.

Why the First Generic Wins Big

The Hatch-Waxman Act didn’t just open the door for generics-it gave the first one a huge advantage. The first generic company to successfully challenge a patent gets 180 days of exclusive market access. During that time, no other generic can enter. Pharmacists are required by law in most states to substitute the generic for the brand, so that first mover captures nearly all the sales.

This incentive has led to a race. Companies like Teva, Mylan, and Sandoz spend millions on legal teams just to be the first to file a Paragraph IV challenge. The payoff? A single drug can generate over $1 billion in revenue during those 180 days. That’s why so many patent battles happen before a drug even hits shelves.

The Orange Book and Patent Thickets

The FDA maintains the Orange Book, a public list of all approved drugs and their associated patents. Brand companies must list every patent they believe covers their drug. But here’s where things get messy.

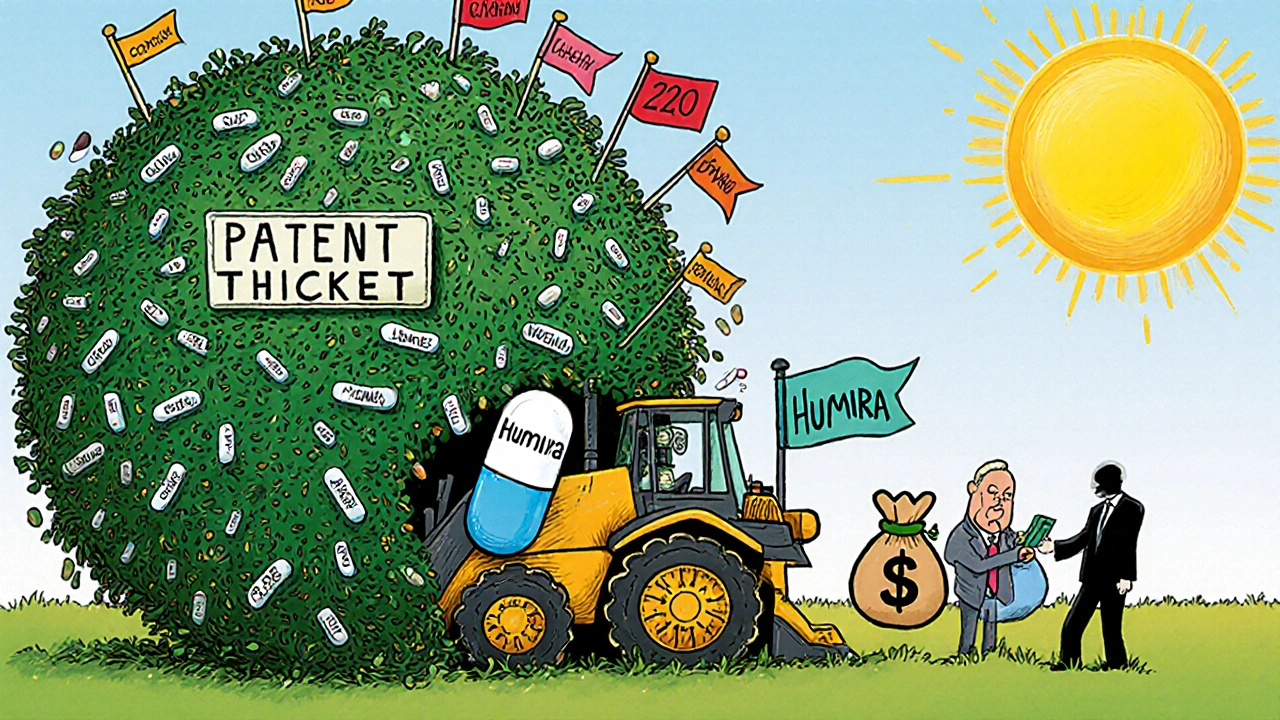

Some companies list dozens of patents-not just for the active ingredient, but for the pill coating, the dosing schedule, the delivery device, or even the manufacturing process. This is called patent thicketing. Take Humira, the anti-inflammatory drug. By the time its main patent expired in 2023, it had over 240 patents listed in the Orange Book. That’s not innovation-it’s a legal wall.

These tactics delay generic entry by years. While Humira was available in Europe as early as 2018, U.S. patients waited five more years. The system was meant to encourage innovation, but it’s often used to extend monopolies.

Generics Save Billions-But at What Cost?

Once generics enter, prices drop fast. The first generic typically cuts the price by 70% within six months. By the time five or six generics are on the market, the price can fall by 90%.

Take Prozac. When Eli Lilly’s patent expired in 2001, the company lost 70% of its U.S. market share and $2.4 billion in annual sales. But patients saved billions. Today, 91% of all prescriptions in the U.S. are filled with generics. Yet they account for only 24% of total drug spending. In 2022 alone, generics saved the U.S. healthcare system $373 billion.

Compare that to ibuprofen. When Boots’ Brufen patent expired in the 1980s, generic versions from Advil and Motrin flooded the market. The price dropped from over $10 per bottle to less than $1. The drug didn’t change. The science didn’t change. Only the label did.

Evergreening and the Ethics of Patent Extensions

Not all patent strategies are created equal. Some companies file new patents on minor changes to an existing drug-like switching from a tablet to a liquid, or changing the release time. This is called evergreening.

The European Commission has called these tactics abusive when they’re used solely to block competition. In the U.S., the practice is legal-but increasingly controversial. The FTC has investigated dozens of cases where brand companies made deals with generics to delay entry. These “pay-for-delay” agreements cost consumers an estimated $3.5 billion a year.

Legislation like the Preserve Access to Affordable Generics and Biosimilars Act aims to ban these deals. But enforcement is slow, and loopholes remain. Until courts and Congress act, the system will keep favoring those with the deepest pockets.

The Future: Biosimilars and Legal Uncertainty

The same patent system that works for pills doesn’t always work for biologics-complex drugs made from living cells, like insulin or cancer treatments. The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) was meant to create a smoother path for biosimilar generics. But in 2017, a federal court ruling in Amgen v. Sandoz threw it into chaos.

The court said brand companies didn’t have to share their manufacturing details with generics. That broke the “patent dance”-a step-by-step process designed to resolve disputes before litigation. Now, biosimilar makers face longer delays and higher legal costs. As a result, only a handful of biosimilars have reached the U.S. market, even though they’ve been available in Europe for years.

Recent laws like the CREATES Act try to fix this by forcing brand companies to provide samples to generics. But without clearer rules, the system remains unpredictable.

Who Wins? Who Loses?

Brand pharmaceutical companies argue that without strong patents, innovation dies. They point to $83 billion spent annually on R&D. Without the promise of exclusivity, they say, no one would risk developing new cancer drugs or Alzheimer’s treatments.

Generic manufacturers counter that the system is rigged. They cite the $2.2 trillion in healthcare savings from generics between 2010 and 2020. They argue that patents should protect true innovation-not minor tweaks.

Patients and taxpayers are caught in the middle. They pay higher prices for longer, while waiting for the next breakthrough. And when a patent finally expires, they get the benefit-but only after years of delay.

The truth is, patent law isn’t broken. It’s working exactly as designed. But the design was made for a different time. Today’s drug market is more complex, more expensive, and more concentrated than ever. The challenge isn’t to eliminate patents-it’s to fix how they’re used.

For now, the system still delivers: new drugs get developed, and eventually, they become cheap. But the road between those two points is longer, more expensive, and more legally tangled than it should be.

How long does a pharmaceutical patent last?

A pharmaceutical patent lasts 20 years from the date it’s filed. But because drug development takes 10-12 years on average, the actual time a company can sell the drug without competition is usually only 8-12 years. Some companies can extend this through patent term restoration if they faced delays during FDA review.

What is the Hatch-Waxman Act?

The Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 is a U.S. law that balances drug innovation and access. It lets generic drug makers apply for approval before a brand patent expires, allows them to challenge patents via Paragraph IV certification, and grants the first successful challenger 180 days of exclusive marketing rights. It also lets brand companies extend their patent term to make up for FDA review delays.

Why do generics cost so much less than brand drugs?

Generics cost 80-85% less because they don’t have to repeat expensive clinical trials. They prove they’re bioequivalent to the brand drug-meaning they work the same way in the body. Their savings come from skipping the R&D costs, which can exceed $2 billion. Once multiple generics enter the market, competition drives prices even lower, sometimes by 90%.

What is patent thicketing?

Patent thicketing is when a drug company files dozens of patents on minor variations of a single drug-like different dosages, delivery methods, or packaging. This creates a legal barrier that makes it hard for generics to enter without facing multiple lawsuits. Humira, for example, had over 240 patents listed, delaying biosimilar competition for years.

Can generics challenge patents before they expire?

Yes. Under the Hatch-Waxman Act, generic companies can file a Paragraph IV certification, claiming a patent is invalid or won’t be infringed. This triggers a 45-day window for the brand company to sue. If they do, FDA approval is automatically stayed for up to 30 months, regardless of whether the patent is actually weak.

What’s the difference between a patent and regulatory exclusivity?

A patent is granted by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office and protects the invention itself. Regulatory exclusivity is granted by the FDA and blocks competitors from using the drug’s data to get approval-even if no patent exists. For example, a new chemical entity gets five years of exclusivity, while orphan drugs get seven. These can run alongside or after patents.

Do patents stifle innovation in the long run?

They can. When companies focus on extending patents through minor changes instead of developing new treatments, innovation slows. The most valuable patents are those that protect truly novel drugs-not tweaks. But without any protection, companies wouldn’t invest in risky, high-cost research. The goal is balance: enough protection to incentivize breakthroughs, but not so much that it blocks access.

Chris Ashley

Bro, I just got my generic Adderall for $4 and I’m not even mad. The brand used to cost me $300 a month. Patents? More like profit locks. 🤡

kshitij pandey

Very nice article! In India, we see generics save lives every day. My uncle took generic insulin for years - cheap, safe, and worked just fine. Innovation is good, but people need medicine more than corporate profits. 🙏

Brittany C

Patent term restoration under 35 U.S.C. § 156 is a critical mechanism to offset regulatory delay - but the cumulative effect of Orange Book listings creates artificial market fragmentation. The FTC’s 2023 report noted 78% of 180-day exclusivity periods were exploited via litigation delays rather than genuine innovation.

Sean Evans

Wow. So the system is literally designed to screw patients? 🤦♂️

Big Pharma spends $83B on R&D? Cool. And then they spend $500B on marketing and legal teams to block generics. You call that innovation? I call it extortion with a lab coat. 🚫💊

Anjan Patel

Let me tell you something - this whole system is a scam! The same companies that make $20 billion off Humira then turn around and pay generic makers millions to NOT come out with cheaper versions! That’s not capitalism - that’s mafia economics. And the FDA? They’re just sitting there like a bored librarian. 😤

Scarlett Walker

I love that generics exist. My mom’s blood pressure med went from $120 to $5. She’s still alive because of it. 🥹

Patents are cool, but not if they cost people their health. We need better balance, not more loopholes.

Hrudananda Rath

It is an incontrovertible fact that the American pharmaceutical regulatory apparatus, while ostensibly structured to incentivize innovation, has, in practice, devolved into a labyrinthine mechanism of rent-seeking behavior, wherein intellectual property rights are weaponized to perpetuate monopolistic control over essential therapeutics. The moral calculus is, frankly, abhorrent.

Brian Bell

Just saw a post about someone getting their generic COPD meds for $2.50. That’s wild. 🤯

Patents are fine, but when you’ve got 240 of them on one drug? That’s not innovation. That’s a legal tangle. 😅

Ryan Anderson

Patent thicketing is a clear abuse of the system. The Hatch-Waxman Act was intended to foster competition, not enable strategic litigation. The FTC has repeatedly flagged these practices as anticompetitive - yet enforcement remains inconsistent. Structural reform is overdue.

Don Ablett

The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act was meant to streamline biosimilar entry yet the Amgen v Sandoz ruling created a de facto barrier by removing the mandatory information exchange. This has significantly delayed market entry and increased litigation costs without enhancing safety or efficacy

Kevin Wagner

Let’s be real - if you’re a billionaire CEO making $10B off one drug, you don’t care about patients. You care about your yacht. 🛥️

Generics are the people’s win. The system’s rigged, but we’re fighting back. Keep pushing for reform, folks. 💪🔥

gent wood

The tension between innovation and access is not a new one, but it has reached a critical inflection point. The economic incentives are misaligned, and the legal architecture is increasingly outmoded. There must be a recalibration - not abolition - of patent protections to ensure equitable access without disincentivizing research.

Dilip Patel

USA think they own every patent in world. India make cheap medicine for whole planet and USA call us thief? LOL. Your drugs cost 10x because you let pharma run everything. We save lives, you save profits. #IndiaStrong

Jane Johnson

The notion that generics are somehow 'equivalent' is a regulatory fiction. Bioequivalence does not guarantee therapeutic equivalence in all populations. The data is insufficient to support blanket substitution.

Barry Sanders

Patents are a joke. If you can't innovate without a 20-year monopoly, you never should've entered the industry. This isn't medicine - it's a casino where patients are the chips.