Amebiasis Risk Assessment Calculator

Your Amebiasis Risk Level

Prevention Tips

Key Takeaways

- Amebiasis causes an estimated 55,000 deaths each year, mostly in low‑resource settings.

- Contaminated water and poor sanitation are the main transmission routes.

- Metronidazole remains first‑line treatment, but rising drug resistance is a growing concern.

- Travelers to endemic regions should take simple water‑safety steps to avoid infection.

- Improved sanitation, rapid diagnostics, and new drug pipelines could cut the disease burden dramatically.

When you hear about Amebiasis is a parasitic infection caused by the protozoan Entamoeba histolytica (the disease‑causing strain of the genus Entamoeba). It spreads through contaminated food or water and can range from mild diarrhea to life‑threatening liver abscesses.

The disease isn’t a rare curiosity; the World Health Organization (WHO) reports that over 50 million people are infected worldwide each year. That translates to roughly 55,000 deaths and a huge number of disability‑adjusted life years (DALY (a metric that combines years of life lost and years lived with disability)) lost annually.

Why Amebiasis Still Matters in 2025

Even though antibiotics have been around for decades, amebiasis remains a stubborn public‑health problem because it thrives where water sanitation (access to clean, safe drinking water and proper waste disposal) is lacking. In many low‑ and middle‑income countries (LMICs (countries with gross national income per capita between $1,036 and $12,535)), people still rely on untreated surface water for drinking and cooking.

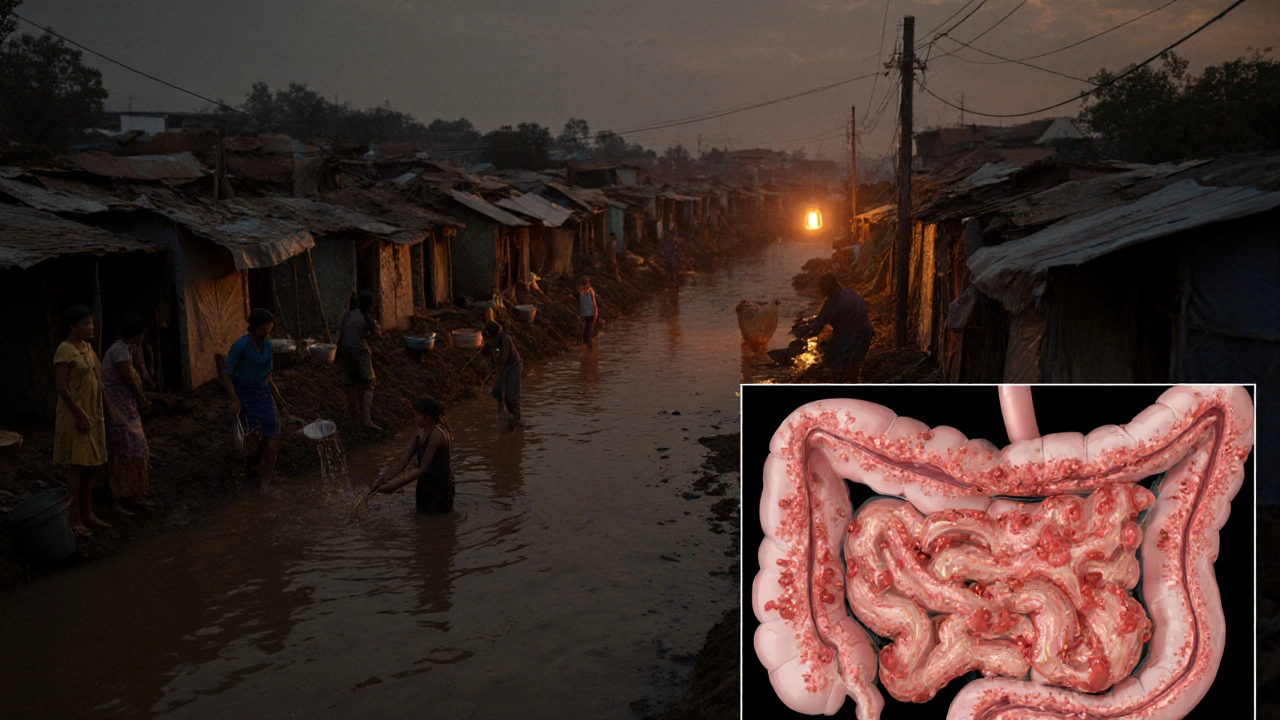

Urban slums, refugee camps, and remote rural villages create perfect conditions for the parasite to spread. Recent climate‑change‑driven flooding events have also surged the number of outbreaks, as floodwaters mix with sewage and contaminate drinking supplies.

Epidemiology: Who Gets Infected?

Children under five and men of working age account for the bulk of cases. School‑age children often pick up the parasite from contaminated school meals, while men in agricultural or construction jobs are exposed through soil and water contact.

Geographically, the highest burden sits in South Asia (India, Bangladesh, Pakistan), Sub‑Saharan Africa (Nigeria, Kenya, Cameroon), and parts of Central America (Mexico, Guatemala). In 2023, a WHO surveillance report highlighted a 12% rise in reported cases in South‑East Asia, driven largely by rapid urbanization without parallel upgrades in water infrastructure.

Clinical Spectrum: From a Tummy Ache to a Deadly Liver Abscess

Most infections are asymptomatic. When symptoms appear, they usually start as watery or bloody diarrhea, abdominal cramps, and occasional fever. If the parasite breaches the intestinal wall, it can travel to the liver, forming a painful abscess that may rupture and cause peritonitis.

Severe disease often requires hospitalization, intravenous fluids, and sometimes surgical drainage of liver abscesses. The mortality risk jumps to over 20% in patients who develop complications and lack timely care.

Current Treatment Landscape

The go‑to drug is Metronidazole (an antiprotozoal medication that penetrates tissue and kills the trophozoite form of Entamoeba histolytica). A typical course lasts 7-10 days, followed by a luminal agent (like paromomycin) to clear cysts from the gut.

However, alarming signals of drug resistance (the reduced efficacy of a drug due to genetic changes in the parasite) have emerged in parts of Indonesia and Brazil. Researchers have identified mutations in the parasite’s pyruvate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase (PFOR) enzyme that lower metronidazole’s killing power.

Because the pipeline for new antamoebic drugs is thin, the WHO has flagged amebiasis as a priority for antimicrobial‑resistance research.

Prevention: Simple Steps That Save Lives

Good hygiene is the cheapest defense. Boiling water for at least one minute, using chlorine tablets, or filtering with a 0.2‑micron filter can eliminate cysts. Hand‑washing with soap before meals and after using the toilet cuts transmission dramatically.

In endemic regions, governments are rolling out community‑level water treatment plants and latrine programs. Education campaigns in schools teach children to avoid unpeeled fruits and to wash vegetables thoroughly.

For travelers, the Travel medicine (the field focusing on health advice and preventive measures for international travelers) community recommends carrying a portable water filter, drinking only bottled or boiled water, and steering clear of street food that hasn't been cooked hot.

Comparing Amebiasis with Other Common Diarrheal Diseases

| Disease | Annual Cases (Millions) | Deaths per Year | Primary Treatment | Major Transmission Route |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amebiasis | 55 | 55,000 | Metronidazole + luminal agent | Contaminated water/food |

| Cholera | 14 | 95,000 | Rehydration + doxycycline | Vibrio cholerae in water |

| Typhoid Fever | \n11 | 130,000 | Ciprofloxacin or azithromycin | Salmonella Typhi via food |

| Rotavirus | 150 | ≈200,000 (mostly children) | Rehydration, vaccine prevention | Fecal‑oral route |

While cholera and typhoid often dominate headlines, amebiasis quietly claims a comparable share of mortality, especially where health systems are weak. Unlike rotavirus, which has an effective vaccine, there is still no licensed vaccine for amebiasis.

Future Outlook: What Could Cut the Burden?

- Rapid point‑of‑care diagnostics: New antigen‑based kits can deliver results in under 15 minutes, allowing quicker treatment.

- Vaccine research: Several Phase I trials of a recombinant vaccine targeting the Gal/GalNAc lectin protein are underway, showing promising immune responses.

- Improved water infrastructure: The UN’s Sustainable Development Goal 6 aims for universal safe water by 2030; meeting it would slash amebiasis rates dramatically.

- Antimicrobial stewardship: Monitoring metronidazole use and developing alternative drugs (e.g., nitazoxanide derivatives) can curb resistance.

In short, tackling amebiasis requires both medical advances and basic public‑health investments. When clean water, reliable diagnostics, and effective treatments align, the disease can move from a persistent threat to a preventable nuisance.

Frequently Asked Questions

How is amebiasis transmitted?

The parasite spreads when people ingest cysts in contaminated water, raw vegetables, or undercooked meat. Poor sanitation and hand‑to‑mouth contact are the biggest risk factors.

What are the early signs I should watch for?

Mild cases may show no symptoms. When they do appear, look for watery or bloody diarrhea, stomach cramps, fever, and occasional nausea. If you notice blood in stool or persistent fever, seek medical care promptly.

Can amebiasis be cured?

Yes. A standard course of metronidazole followed by a luminal drug clears the infection in most patients. Severe cases may need hospitalization and surgical drainage of liver abscesses.

Is there a vaccine for amebiasis?

Not yet. Researchers are testing several vaccine candidates, but none have reached market approval. Prevention still relies on clean water and hygiene.

What should travelers to endemic areas do?

Carry a portable water filter or purification tablets, drink only bottled or boiled water, avoid raw salads and unpeeled fruits, and wash hands with soap before eating.

Mary Cautionary

One must acknowledge the exquisite intricacy of amebiasis as a paradigmatic exemplar of neglected tropical maladies, wherein the confluence of substandard sanitation and microbial tenacity manifests in a public‑health quandary of disquieting proportions. The epidemiological data delineated within the article is both compelling and meticulously curated, reflecting a commendable dedication to scholarly rigour. Yet, the exposition could benefit from a more nuanced interrogation of the sociopolitical determinants that perpetuate water insecurity in endemic locales. Moreover, a discourse on the ethical imperatives of pharmaceutical investment in antiparasitic research would enrich the narrative. In sum, the treatise stands as a salient contribution to global‑health literature, notwithstanding the modest lacunae noted herein.

Crystal Newgen

I appreciated the clear breakdown of risk factors; the calculator idea is user‑friendly and could aid travelers in making informed choices.

Hannah Dawson

This piece glosses over the glaring inadequacies of current diagnostic modalities, which remain painfully slow and insufficiently sensitive. It also sidesteps the alarming emergence of metronidazole‑resistant strains in regions like Indonesia, a fact that demands urgent attention. The author’s optimism about vaccine pipelines feels premature given the modest progress reported in Phase I trials. Furthermore, the lack of discussion on socioeconomic inequities that drive exposure is a glaring omission. Overall, the article reads like a superficial overview rather than a critical analysis.

Julie Gray

One cannot ignore the covert machinations of multinational water corporations, whose profit motives subtly undermine genuine public‑health interventions. The so‑called "risk calculator" may simply serve to shift responsibility onto individual travelers while absolving systemic failings.

Lisa Emilie Ness

Great summary.

Emily Wagner

From a pseudo‑philosophical lens, amebiasis epitomizes the dialectic between human agency and microbial determinism. The pathogen's life cycle functions as a metaphor for entropy in socio‑environmental systems. Intervention strategies, therefore, must grapple with both biochemical pathways and the broader ontological frameworks that shape disease perception. The article rightly underscores water safety, yet fails to interrogate the epistemic gaps in our collective understanding of parasitic resilience. Integrating systems thinking could yield more holistic solutions. In essence, the fight against Entamoeba histolytica is as much a battle of ideas as it is of medicine.

Mark French

It’s realy important to get treatment quick if u have symptoms. Metronidazole works well but you gotta follow up with a lumenal drug. Stay safe and wash hands!

Daylon Knight

Oh sure, because everyone loves a good water filter while trekking through a slum. No big deal, right?

Jason Layne

The narrative presented is a shameless cover‑up of a coordinated attempt to keep populations dependent on low‑cost pharmaceutical fixes. You will notice the selective omission of the pharmaceutical lobby’s influence on WHO guidelines. The push for metronidazole perpetuates a monopoly that stifles innovation. It’s no coincidence that resistance hotspots align with regions where profit‑driven trials are absent. The article’s feigned objectivity is a veneer for systemic negligence.

Hannah Seo

For anyone seeking practical guidance, I recommend the following: always boil water for at least one minute, use chlorine tablets when boiling isn’t feasible, and carry a portable filter for on‑the‑go trips. Hand‑washing with soap should be performed before every meal and after any restroom use. Travelers should avoid raw salads and unpeeled fruits unless you can verify they’ve been properly washed or cooked. If you develop persistent diarrhea or notice blood in stool, seek medical evaluation promptly. Early treatment with metronidazole followed by a luminal agent such as paromomycin is highly effective. Education on these steps can dramatically lower infection risk.

Marcia Hayes

Stay hydrated and keep those hands clean!

Danielle de Oliveira Rosa

Reflecting upon the interdependence of sanitation infrastructure and disease prevalence invites a compassionate inquiry into the lived realities of those in endemic regions. It is incumbent upon us, as global citizens, to recognize that the microscopic journey of Entamoeba histolytica mirrors the macro‑social currents of inequality. By fostering dialogues that bridge scientific knowledge with ethical stewardship, we may cultivate a more equitable health paradigm. The article serves as a catalyst for such discourse, albeit with room for deeper philosophical engagement.

Tarun Rajput

Embarking upon a comprehensive exposition of amebiasis necessitates a deliberate traversal through a labyrinth of interwoven themes, each demanding meticulous articulation and unwavering scholarly vigor. First, the historical trajectory of Entamoeba histolytica elucidates a saga of parasitic endurance, showcasing evolutionary adaptations that have enabled it to flourish across disparate ecological niches, from the stagnant backwaters of the Ganges delta to the bustling irrigation canals of the Brazilian interior.

Second, the epidemiological canvas reveals a stark tableau of burden distribution, wherein low‑ and middle‑income nations disproportionately shoulder the morbidity and mortality, a pattern inexorably linked to deficits in potable water access and inadequate sewage disposal mechanisms.

Third, the pathogen’s pathogenic mechanisms, characterized by trophozoite invasion of the colonic epithelium and subsequent hepatic dissemination, underscore a sophisticated interplay of virulence factors, including the Gal\/GalNAc lectin, cysteine proteases, and amoebapores, each orchestrating tissue destruction with alarming precision.

Fourth, the clinical spectrum, ranging from asymptomatic cyst carriage to fulminant dysentery and pyogenic liver abscesses, demands a nuanced diagnostic algorithm that incorporates stool antigen detection, polymerase chain reaction assays, and imaging modalities for extra‑intestinal manifestations.

Fifth, therapeutic regimens, anchored by metronidazole and complemented by luminal agents such as paromomycin, confront emerging challenges posed by genetic mutations in the parasite’s PFOR enzyme, heralding the specter of drug resistance that necessitates vigilant surveillance and innovative drug development pipelines.

Sixth, preventive strategies, anchored in the triumvirate of water purification, rigorous hand hygiene, and community education, emerge as the most cost‑effective bulwark against transmission, particularly when synergized with infrastructural investments aligned with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 6.

Seventh, the promising frontier of vaccine research, exemplified by recombinant Gal‑lectin constructs and nanoparticle‑based delivery systems, offers a glimmer of hope, though extensive phase II/III trials remain requisite to ascertain efficacy and safety across diverse demographic cohorts.

Eighth, the socioeconomic dimensions, encompassing gendered labor patterns that expose men in agrarian contexts to contaminated water sources, and the vulnerability of children in overcrowded urban slums to fecal‑oral exposure, illuminate the imperative for gender‑responsive and child‑focused interventions.

Ninth, the policy landscape calls for robust intergovernmental collaboration, integrating WHO surveillance data with national health ministries to forge adaptive response frameworks that can swiftly mobilize resources during outbreak surges precipitated by climate‑induced flooding events.

Tenth, the ethical considerations surrounding equitable access to diagnostics and therapeutics compel a moral reckoning, urging stakeholders to eschew market‑driven monopolies in favour of shared intellectual property models that democratize life‑saving technologies.

Eleventh, the educational component, leveraging school curricula to inculcate safe water practices and personal hygiene from an early age, can engender generational shifts in behavioural norms that curtail transmission cycles.

Twelfth, the role of digital health platforms, through real‑time symptom reporting and geospatial mapping of case clusters, promises to augment traditional epidemiological surveillance with precision analytics.

Thirteenth, the integration of community health workers, equipped with rapid antigen kits, can bridge the gap between formal healthcare facilities and remote populations, fostering timely case detection and treatment initiation.

Fourteenth, the importance of interdisciplinary research, uniting parasitologists, water engineers, sociologists, and economists, cannot be overstated, as it cultivates holistic solutions that transcend singular domain silos.

Fifteenth, sustained investment in capacity building, encompassing laboratory infrastructure and skilled personnel training, is indispensable for sustaining long‑term gains in amebiasis control.

In summation, the confluence of scientific insight, infrastructural commitment, and social equity forms the cornerstone of an ambitious yet attainable vision: to relegate amebiasis from a persistent global health menace to a preventable footnote in the annals of human disease.