When a pharmacist hands a patient a new bottle of medication labeled as a generic version of their usual prescription, most assume it’s just a cheaper copy of the same thing. But for NTI generics, that assumption can be dangerous. Narrow Therapeutic Index drugs-like warfarin, levothyroxine, and phenytoin-have a razor-thin margin between a safe dose and a toxic one. A 10% difference in how the body absorbs the drug can mean the difference between effective treatment and hospitalization. And yet, across the U.S., pharmacists are seeing more of these substitutions happen without warning, without monitoring, and sometimes without consent.

What Makes a Drug an NTI Drug?

NTI stands for Narrow Therapeutic Index. These are drugs where even tiny changes in blood concentration can lead to serious harm. For example, warfarin, a blood thinner, requires precise dosing to prevent clots without causing internal bleeding. Too little, and a stroke might occur. Too much, and a patient could bleed out. Levothyroxine, used for hypothyroidism, needs to maintain thyroid hormone levels within a very tight range-small fluctuations can trigger heart problems, weight changes, or depression. Phenytoin, an anti-seizure drug, has similar risks: too low, and seizures return; too high, and the patient may lose coordination, develop tremors, or even fall into a coma.

The FDA doesn’t publish an official list of NTI drugs, but it does flag them in the Orange Book with therapeutic equivalence codes. Drugs marked with a "B" code are flagged as potentially problematic for substitution. As of 2025, 42 drugs have been identified by researchers as needing stricter bioequivalence standards, and 15 of those have already shown clear clinical consequences when switched between generic versions.

Why Are Pharmacists Worried?

Pharmacists aren’t resisting generics out of loyalty to brand names. They’re worried because the current system doesn’t guarantee therapeutic equivalence for NTI drugs. Standard generics must prove they’re 80% to 125% as bioavailable as the brand-name drug. For NTI drugs, that range is too wide. The FDA recommends a tighter 90% to 111% range for drugs like warfarin and phenytoin, but that’s not always enforced-or even tracked.

A 2024 survey by the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists found that 68% of pharmacists have concerns about substituting NTI generics. That number jumps to 73% among community pharmacists who report being asked by doctors to avoid substitutions. In one hospital in Ohio, a patient on a stable dose of levothyroxine switched to a different generic brand and developed atrial fibrillation within two weeks. Her TSH levels dropped from 2.1 to 0.3-well outside the therapeutic range. She needed emergency treatment.

It’s not just one bad batch. The FDA’s Adverse Event Reporting System recorded 1,247 adverse events linked to NTI generic substitutions between 2020 and 2024. For non-NTI generics, that number was 382. That’s more than triple the risk.

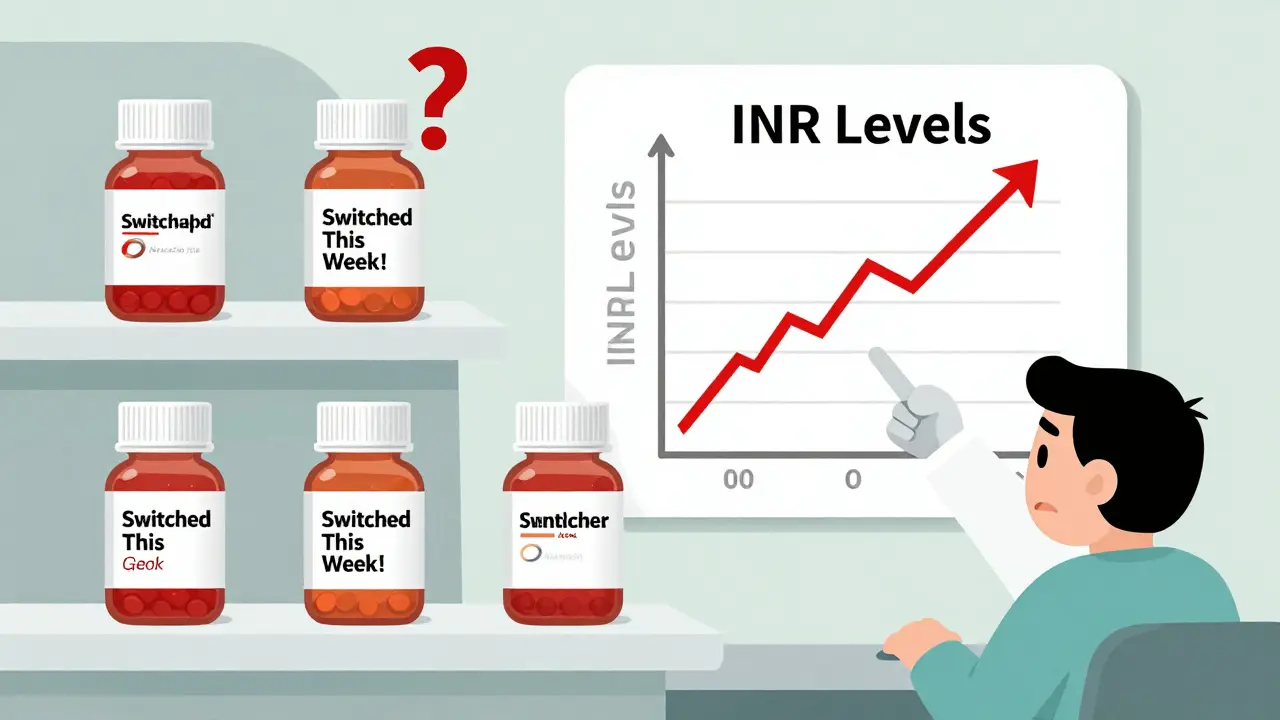

Switching Between Generics Is the Real Problem

One of the biggest issues isn’t switching from brand to generic-it’s switching between different generic manufacturers. A patient might start on one generic warfarin, then get refilled with another because the first one was out of stock. Or the pharmacy switches suppliers based on price. Each switch introduces new variability in fillers, binders, and manufacturing processes. Even if each generic meets FDA standards individually, they’re not necessarily interchangeable with each other.

The FDA itself reported in 2024 that 23% of NTI drug shortages were worsened by frequent switching between manufacturers. Hospitals and pharmacies are forced to rotate stock to manage costs, but for NTI drugs, that’s like playing Russian roulette with patient stability.

A 2024 study from the University of Florida found that 34% of pharmacists would refuse to automatically substitute warfarin generics, compared to just 8% for non-NTI drugs. For levothyroxine, 29% of pharmacists say they only dispense the same brand unless the prescriber specifies otherwise. That’s not conservatism-it’s clinical caution.

The Cost vs. Risk Trade-Off

Generics save money. There’s no denying that. NTI generics cost 80% to 85% less than brand-name versions. For patients on fixed incomes, that’s life-changing. One independent pharmacy owner in Ohio told me he saw a 35% drop in patients abandoning their prescriptions after switching to generics. That’s a win.

But the savings come with hidden costs. When a patient has to be hospitalized due to an INR spike after a generic switch, the bill can exceed $15,000. Add in lost wages, follow-up visits, and long-term complications, and the cost savings vanish. One hospital system in Texas tracked 14 NTI-related admissions over 18 months-all preventable. The cost of those admissions was 12 times what they saved by switching to cheaper generics.

It’s not just about money. It’s about trust. Patients rely on pharmacists to keep them safe. When a pharmacist has to explain why they can’t switch a drug-even if it’s legally allowed-they’re caught between policy and patient safety.

State Laws Are a Patchwork

There’s no national standard for NTI drug substitution. As of January 2025, only 28 states have laws restricting automatic substitution of NTI drugs. Twenty-two states require prescriber approval before switching. Six states ban automatic substitution entirely. The rest? No rules. That means a patient in Florida might get a different generic than the same patient in California, even if they’re on the same prescription.

Pharmacists in states without restrictions feel powerless. A survey by the National Community Pharmacists Association found that 61% of pharmacists want state laws to require prescriber notification before substituting NTI drugs. Only 29% want that for non-NTI drugs. The difference is clear: pharmacists know NTI drugs need special handling.

What Pharmacists Are Doing About It

Despite the lack of clear rules, many pharmacies are taking matters into their own hands. The ASHP’s 2025 Toolkit recommends maintaining a single source for NTI drugs whenever possible. Sixty-three percent of hospital systems now do this-locking in one generic manufacturer for each NTI drug and refusing to switch unless absolutely necessary.

Some pharmacies use color-coded labels or special alerts in their electronic systems to flag NTI prescriptions. Others require prescribers to write "Dispense as Written" or "No Substitution" on the prescription. In hospital settings, pharmacists are increasingly involved in therapeutic drug monitoring, checking INR levels, TSH, or phenytoin concentrations after any switch.

Pharmacy residency programs are responding, too. In 2024, 81% of accredited pharmacy residencies added NTI drug management to their curriculum. That’s up from 45% just five years ago. Pharmacists are being trained not just to dispense, but to monitor, communicate, and advocate.

What’s Changing in 2025 and Beyond

The FDA announced a new bioequivalence framework in April 2025, targeting 12 high-priority NTI drugs with stricter testing standards by 2026. This includes mandatory chiral separation testing for drugs with stereoisomers-something many generic manufacturers currently skip. It’s a step forward, but many pharmacists say it’s still not enough.

Meanwhile, the Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program is including three NTI drugs in its first round of price caps. That’s good for affordability-but Lisa Schwartz of the NCPA warned that the 21-day reimbursement delay could cause cash flow problems for small pharmacies. If they can’t afford to stock the drug, patients go without. And for NTI drugs, going without is not an option.

Research from the University of Minnesota shows that 80% of generic drugs are finished overseas. For NTI drugs, that number is even higher. Supply chains are fragile. A single factory shutdown in India or China can trigger a nationwide shortage. The FTC is now investigating group purchasing organizations that bundle NTI drugs into bulk contracts, often forcing pharmacies to switch brands without notice.

Looking ahead, 74% of healthcare systems plan to launch pharmacist-led NTI drug stewardship programs by 2027. That means pharmacists won’t just be dispensers-they’ll be clinical decision-makers, tracking labs, coordinating with prescribers, and managing substitutions with patient safety as the top priority.

What Patients Should Know

If you’re on warfarin, levothyroxine, phenytoin, or another NTI drug, here’s what you need to do:

- Ask your pharmacist: "Is this the same generic I’ve been taking?" If they say "I don’t know," ask to speak to the pharmacist in charge.

- Check your prescription label. If it lists a different manufacturer than usual, ask if it’s safe to switch.

- Don’t assume a cheaper version is automatically better. If you feel different after a switch-fatigued, anxious, dizzy, or unwell-tell your doctor and pharmacist immediately.

- Request a "Dispense as Written" note from your prescriber if you’ve had stability issues in the past.

It’s not about being difficult. It’s about staying safe. For NTI drugs, consistency isn’t a luxury-it’s a necessity.

What Prescribers Should Do

Doctors often don’t realize how much control pharmacists have-or don’t have-over NTI substitutions. If you’re prescribing one of these drugs:

- Write "Dispense as Written" or "No Substitution" on the prescription. It’s legally binding in many states.

- Ask your pharmacy if they use a consistent generic source. If not, consider recommending one.

- Check labs more frequently after any switch-don’t wait for the next scheduled visit.

- Don’t assume your patient knows to tell you if their generic changed. Proactively ask.

For NTI drugs, your prescription isn’t just a request-it’s a safety plan.

Are all generic drugs the same?

No. For most drugs, yes-generics are interchangeable. But for Narrow Therapeutic Index (NTI) drugs like warfarin, levothyroxine, and phenytoin, even small differences in how the body absorbs the drug can cause serious harm. Two generics may both meet FDA standards individually, but switching between them can lead to dangerous fluctuations in blood levels.

Why isn’t there a federal ban on substituting NTI generics?

There’s no federal ban because the FDA considers generics legally equivalent if they meet bioequivalence standards-even if those standards are too broad for NTI drugs. Regulation is left to the states, which is why rules vary widely. Some states require prescriber approval, others allow automatic substitution. The lack of a national standard leaves patients and pharmacists in a patchwork of conflicting rules.

Can I ask my pharmacist to stick with one brand of generic?

Yes. You can ask your pharmacist to dispense the same generic manufacturer every time. Many pharmacies will honor this request, especially for NTI drugs. You can also ask your prescriber to write "Dispense as Written" on your prescription. This legally prevents substitution in most states.

How do I know if my drug is an NTI drug?

Common NTI drugs include warfarin, levothyroxine, phenytoin, carbamazepine, digoxin, cyclosporine, and theophylline. If you’re unsure, ask your pharmacist or check the FDA’s Orange Book. Look for drugs with therapeutic equivalence codes marked "B"-these are flagged as having potential substitution risks.

What should I do if I feel different after switching to a new generic?

Don’t ignore it. Contact your pharmacist and prescriber right away. For NTI drugs, even mild symptoms like fatigue, dizziness, or irregular heartbeat can signal a dangerous change in blood levels. Request a lab test-INR for warfarin, TSH for levothyroxine-to confirm if your levels have shifted. Keep a record of the manufacturer name and lot number on your prescription bottle.

James Hilton

So let me get this straight-we’re risking strokes and heart attacks to save $20 a month? 🤡

Pharmacists are the real MVPs here. Meanwhile, insurance companies are doing the happy dance.

Mimi Bos

i just got my levothyroxine and it was a diffrent brand and i felt so tired and weird like my brain was foggy?? idk if its the med or i just need more coffee 😅

Payton Daily

This whole system is a metaphysical joke. We live in a world where a pill’s filler is more important than your life. The FDA? They’re not regulators-they’re accountants with a medical dictionary. We’ve turned healthcare into a spreadsheet, and now we’re surprised when the numbers bleed?

Phenytoin isn’t a commodity. It’s a lifeline. And yet we treat it like a bulk discount at Walmart. What are we, a nation of bargain hunters or a society that values human stability? I’ll tell you-we’re the kind of people who’ll trade a heartbeat for a coupon.

Bradly Draper

I work in a clinic and I’ve seen this happen. One patient went from stable to crashing because they switched generics. We had to rush her in. It’s not hype. It’s real. And it’s preventable. We need to stop treating these drugs like interchangeable soda brands.

Gran Badshah

in india we dont even have this problem because generics are not allowed to be switched without doctors approval. why usa so chaotic? you have money but no sense

Ellen-Cathryn Nash

Some people think 'cheap' means 'good.' Others understand that when your life hangs on a fraction of a milligram, 'cheap' is just a fancy word for 'reckless.'

It’s not about being anti-generic. It’s about being pro-survival. And if you’re the kind of person who’d rather save $15 than risk a seizure, maybe you should stop making decisions for other people.

Samantha Hobbs

I just switched my warfarin generic and now I’m scared to leave the house. Like… what if I trip and bleed out and no one knows why? 😭

Nicole Beasley

My pharmacist gave me a little card that says "THIS IS YOUR NTI DRUG - DO NOT SWITCH" and I keep it in my wallet 🫶

Best. Pharmacist. Ever.

sonam gupta

USA is broken system everyone want cheap nothing care about patient only profit

Julius Hader

I used to think generics were all the same. Then my mom had a bad reaction after a switch. Now I make sure every single prescription for her has 'Dispense as Written' on it. It’s not being difficult. It’s being responsible.

And if your pharmacy gives you a hard time? Find a new one. Your life’s worth it.

Vu L

You guys are overreacting. It’s just a pill. If your body can’t handle a different filler, maybe you’re the problem. I’ve switched generics my whole life and I’m fine. Stop acting like your thyroid is a sacred relic.