Imagine spending 12 years and $2.6 billion to develop a new drug-only to find out you have just 8 years left on your patent once it finally hits the market. That’s the reality for many pharmaceutical companies. The FDA approval process alone can take up to a decade, eating up precious years of patent life. Without a way to make up for that lost time, companies would have little incentive to invest in new treatments. That’s where patent term restoration (PTE) comes in. It’s not a loophole. It’s a legal fix designed to balance innovation with access.

What Exactly Is Patent Term Restoration?

Patent term restoration, or PTE, is a U.S. law that lets drugmakers get back some of the time they lost waiting for FDA approval. It doesn’t extend the patent forever. It doesn’t create new rights. It simply restores part of the 20-year patent clock that ran while the drug was stuck in regulatory review.

This system was created by the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984. Before this law, drug companies had two bad choices: file patents too early (risking them expiring before approval) or wait until approval (risking competitors copying the drug before they could even launch). Hatch-Waxman solved that by letting companies apply for an extension after approval-up to five years, but with a hard cap: the total patent life after extension can’t go beyond 14 years from the date the FDA approved the drug.

It’s not just for pills. PTE also covers medical devices, food additives, color additives, and animal drugs. Since 1984, over 1,200 extensions have been granted. In 2023 alone, the FDA processed 287 applications. The average wait for approval? About 217 days.

How Is the Extension Calculated?

The math behind PTE isn’t simple, but here’s the basic idea:

- You start with the total time your drug spent under FDA review (Regulatory Review Period).

- You subtract the time before you even filed for patent (Pre-Grant Regulatory Review Period).

- You subtract any days where the FDA says you weren’t moving fast enough (Days of Applicant’s Lack of Due Diligence).

- You also can’t extend past the 5-year limit or beyond 14 years post-approval.

For example: if your drug spent 7 years in FDA review, but 2 of those years were before your patent was filed, and you had 6 months of delays due to incomplete submissions, your extension might be around 4.5 years. But if your patent would have expired in 12 years from approval, you’d only get 2 more years-because 14 is the hard ceiling.

This system forces companies to be precise. One missed document, one unexplained delay, and your application gets denied. The USPTO denied nearly 13% of PTE applications in 2022-mostly because applicants couldn’t prove they were constantly pushing the FDA to review their files.

Who Can Apply? And When?

Only the patent holder can apply-and only if:

- The patent hasn’t expired yet.

- The product was subject to regulatory review before being sold.

- The patent hasn’t been extended before.

- The application is filed within 60 days of FDA approval.

That 60-day window is brutal. Many companies miss it because their legal team and regulatory team aren’t talking. A 2022 study found that 43% of PTE delays happened because patent lawyers didn’t get timely updates from the FDA submission team. That’s not a paperwork issue-it’s a communication breakdown.

There’s also an “interim extension” option. If your patent is about to expire before the FDA gives final approval, you can apply for a temporary extension. This keeps your protection alive while you wait. It’s like a bridge-short-term, but critical.

Why Is PTE Controversial?

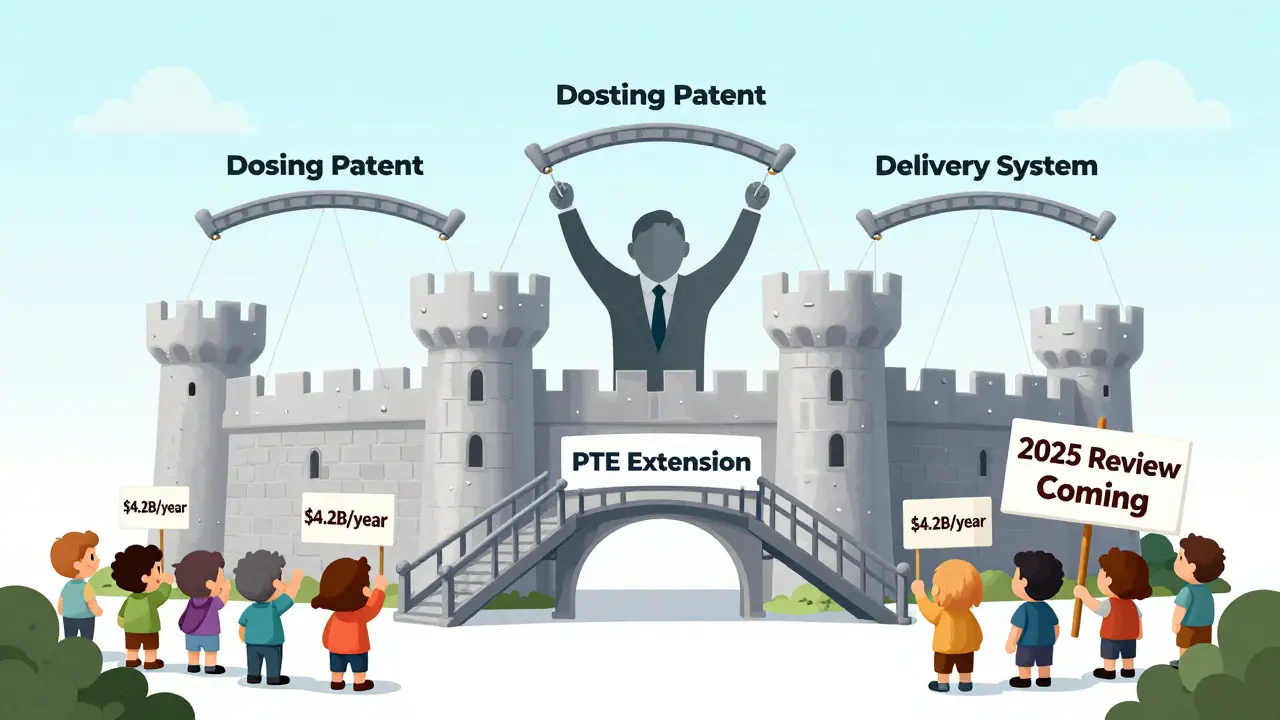

On paper, PTE sounds fair. You lost time. You get it back. But here’s the catch: most PTE applications aren’t for the original patent on the active ingredient. They’re for secondary patents-on delivery methods, dosing schedules, or formulations.

According to JAMA analysis of FDA Orange Book data, 78% of PTE applications in recent years involve these follow-up patents, not the core compound. That means a company might get a 5-year extension on a patent for a pill coating, not the drug itself. Critics call this “evergreening”-using the system to keep generics out longer than Congress intended.

A 2022 Yale study found that 91% of drugs that got a PTE still held a monopoly years after the extension ended, thanks to other patents, exclusivity periods, or legal tactics. The Congressional Budget Office estimates PTE adds $4.2 billion a year to U.S. drug spending by delaying cheaper generics.

But here’s what you won’t hear from big pharma: without PTE, many drugs wouldn’t exist at all. The average development cost is $2.6 billion. If companies couldn’t recover lost patent time, they’d never risk it. PTE isn’t perfect-but it’s what keeps innovation alive.

What’s Changing in 2025-2026?

The rules are tightening. In January 2024, the FDA released new guidance on “due diligence,” making it clearer what counts as continuous progress. The USPTO is also getting stricter. A 2024 Federal Circuit ruling (Eli Lilly v. USPTO) said companies must now show daily logs-not just milestone dates-to prove they weren’t dragging their feet.

There’s also a push to digitize the process. The FDA’s 2024 Strategic Plan says it wants to move PTE applications to an online portal by mid-2026. Right now, applicants still submit paper records, PDFs, and spreadsheets. That’s slow. That’s error-prone. That’s why so many applications get denied.

Biologics-complex drugs made from living cells-are getting more extensions than ever. In 2018, only 19% of PTE applications were for biologics. By 2023, that jumped to 34%. These drugs take even longer to approve, so the need for PTE is growing.

What Happens After the Extension Ends?

Once the extended patent expires, generics can enter the market. But they don’t always come right away. Companies often use other tricks-like citizen petitions, litigation, or exclusivity periods-to delay competition. That’s not PTE’s fault. But it’s why the system gets blamed for high drug prices.

When generics finally arrive, prices drop fast. The FTC found that drugs with PTE hold 92% of the market during the extension. After generics launch? That drops to 37%. That’s the power of competition.

What Should You Know If You’re in Pharma?

If you work in drug development, PTE isn’t optional. It’s part of your business plan. Here’s what you need to do:

- File your patent as early as possible-but not so early that it expires before approval.

- Keep a daily log of every interaction with the FDA. Emails, meeting notes, submission dates. Everything.

- Make sure your patent team and regulatory team are in sync. Weekly check-ins aren’t enough. Daily updates are better.

- Apply for PTE within 60 days of FDA approval. No exceptions.

- Don’t wait until the last minute to gather documents. The FDA and USPTO don’t give extensions.

And if you’re a small company? The FDA’s Small Business Assistance program offers free help. Email [email protected]. They answered over 1,800 questions in 2023. They’ll guide you through the paperwork.

Final Thought: Is PTE Working?

Yes-but not perfectly. It does what it was designed to do: give innovators a fair shot at recouping their investment. But it’s also being used in ways Congress didn’t foresee. The real issue isn’t PTE itself. It’s how it’s layered with other legal tools to stretch monopolies far beyond what’s reasonable.

The Government Accountability Office is set to release a major review of PTE in December 2025. That report could lead to changes-maybe even limits on secondary patents. For now, PTE remains a vital, if imperfect, part of the drug development engine. It’s not about cheating the system. It’s about making sure the system doesn’t kill innovation before it even starts.

Adam Rivera

Man, I remember when my cousin worked at a biotech startup and they missed the 60-day PTE window by three days because the regulatory team forgot to CC the patent lawyer. Lost like $400M in projected revenue. It’s not just bureaucracy-it’s a damn minefield.

Rosalee Vanness

I love how this post breaks down the math without drowning you in legalese. It’s rare to see something this complex explained with both precision and heart. The daily log requirement? That’s not just compliance-it’s survival. Small companies need that FDA SBIA program more than they know.

lucy cooke

Oh, here we go again-the ‘innovation’ narrative. Let’s not pretend PTE is about saving lives. It’s about preserving shareholder dividends under the velvet glove of ‘fair compensation.’ The real tragedy isn’t the 14-year cap-it’s that we’ve normalized pharmaceutical monopolies as if they were natural law. We’re not curing disease; we’re auctioning hope.

John Tran

wait so if you mess up one email thread you lose 5 years? that’s insane. i mean like… what if your intern typo’d the FDA submission date? like… is there no grace period? i feel like this system is designed to fail people who aren’t big pharma lawyers with armies of paralegals. also i think i spelled ‘diligence’ wrong. oops.

Gregory Parschauer

Oh, so now we’re romanticizing patent extensions like they’re some noble sacrifice? Let’s be clear: 78% of these extensions are on coating formulations and pill shapes-NOT THE DRUG ITSELF. You’re not protecting innovation; you’re gaming a loophole designed for penicillin, not $200-a-pill insulin pens. This isn’t fairness. It’s corporate theater with a side of taxpayer-funded greed.

Trevor Davis

As someone who’s seen both sides-worked at a startup that got denied PTE and now consult for Big Pharma-I can say this: the system is broken, but not because of intent. It’s because the players aren’t talking. The regulatory team thinks ‘submit’ means ‘done.’ The legal team thinks ‘patent’ means ‘forever.’ No one checks in. And then everyone blames the law.

James Castner

One must contemplate the ethical architecture of intellectual property in the context of human health. The patent system, born of Enlightenment ideals, was intended to incentivize discovery through temporal exclusivity-not to become a perpetual tollbooth on the highway of medical progress. When secondary patents-on delivery mechanisms, colorants, or packaging-are granted extensions under the guise of ‘regulatory delay,’ we are not merely extending patent life; we are perverting the social contract between innovation and equity. The 14-year ceiling was a compromise. But when 91% of drugs maintain de facto monopolies through layered legal stratagems after PTE expiration, we are no longer balancing interests-we are institutionalizing exploitation. The GAO’s forthcoming review may be our last chance to recalibrate this machinery before it grinds the public’s access to medicine into dust.

vishnu priyanka

in india we don’t even get this luxury. our generics save lives. but i get it-this system keeps the lights on in labs in boston and san diego. still, when a kid in delhi can’t afford his asthma inhaler because of a patent on the *cap*… man. it’s wild.

Lethabo Phalafala

I cried reading this. Not because I’m emotional-though I am-but because I’ve sat in rooms where people argued for 18 hours over whether a single email counted as ‘due diligence.’ This isn’t just policy. It’s life and death. And the people who lose? They’re not in the boardroom. They’re in the ER. I hope someone reads this and changes something.

Acacia Hendrix

It’s fascinating how the Hatch-Waxman Act, while well-intentioned, became the legal substrate for what is essentially a regulatory arbitrage scheme. The asymmetry between the sophistication of patent prosecution and the opacity of FDA due diligence protocols creates a fertile ground for rent-seeking behavior. One must interrogate whether the 5-year cap is truly a constraint-or merely a performative constraint designed to preserve the illusion of equity.

mike swinchoski

Big Pharma doesn’t want you to know this, but most of these PTEs are just fancy legal tricks to keep prices high. They don’t even make the drug better. They just change the color. And you pay more. That’s not innovation. That’s scamming. And if you’re okay with that, you’re part of the problem.

Trevor Whipple

LOL the ‘daily log’ thing? That’s why startups fail. Who has time to write down every single email? I’m just glad I don’t work in pharma. Also typo: ‘diligence’ is spelled with two L’s, not one. Just saying.