If you’ve had heartburn for years - even if it’s "mild" - you might be at risk for something far more serious than discomfort. Chronic GERD isn’t just a nuisance. It’s the strongest known driver of esophageal adenocarcinoma, a type of cancer that’s rising fast and often caught too late. The truth? Most people with GERD won’t get cancer. But if you’ve had it for five years or more, especially with other risk factors, your odds shift dramatically. And the signs that something’s turning dangerous aren’t subtle. They’re clear. You just have to know what to look for.

How GERD Turns Into Cancer

GERD means stomach acid keeps backing up into your esophagus. Your esophagus isn’t designed to handle that. Over time, the constant burn triggers a survival response: the lining starts changing. It begins to look more like stomach tissue. This is called Barrett’s esophagus. It’s not cancer. But it’s the only known precursor to esophageal adenocarcinoma. And once it’s there, the risk of cancer doesn’t disappear - it grows.

According to a major 2023 study from the NIH, people with chronic GERD have more than three times the risk of developing esophageal cancer compared to those without it. That’s not a small bump. That’s a steep climb. And it doesn’t matter if you’re on medication. If you’ve had reflux for five or more years - even if you’re taking PPIs - your risk stays elevated. The body doesn’t forget the damage. The cells keep trying to adapt. And sometimes, those adaptations go wrong.

Who’s Really at Risk?

Not everyone with GERD is equal. The risk isn’t random. It clusters around specific, measurable factors. If you’re a white male over 50 with long-term GERD, you’re in the highest-risk group. But it’s not just age and gender. It’s the combo.

- Male sex: Men are 3 to 4 times more likely than women to develop this cancer.

- Age 50+: Nine out of ten cases happen in people over 55.

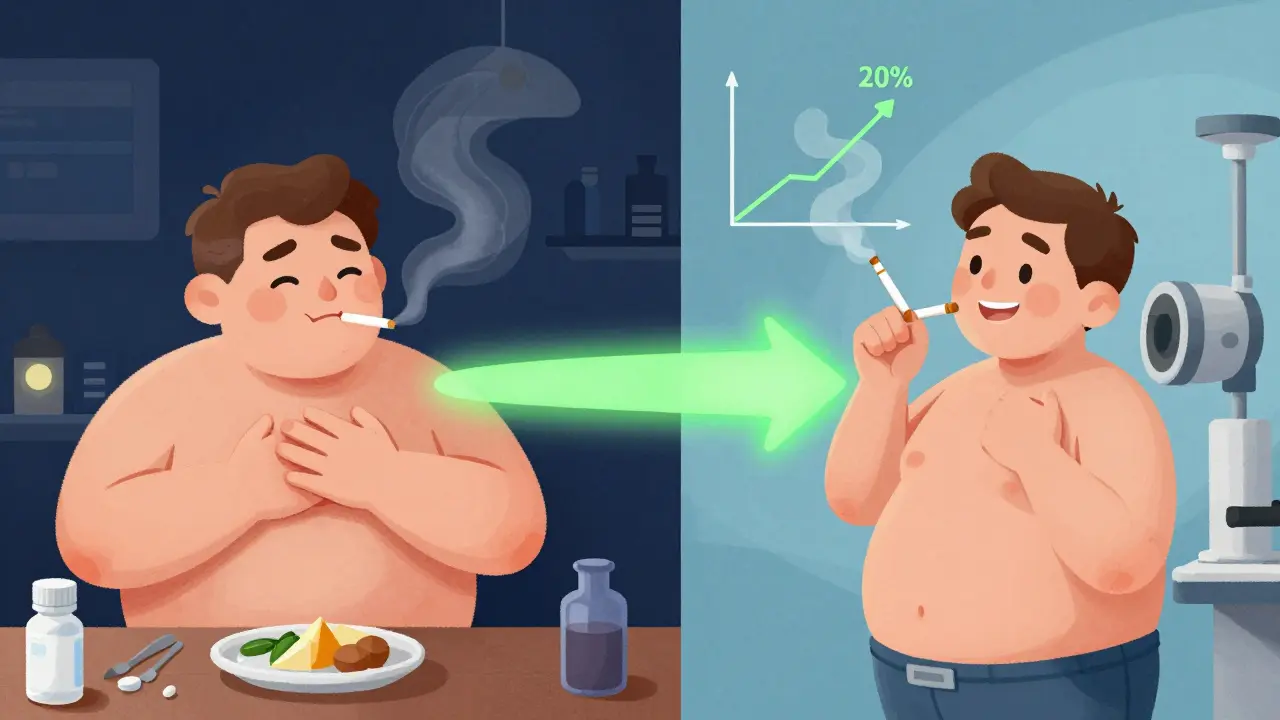

- Obesity: A BMI over 30 doubles or triples your risk by increasing pressure on your stomach.

- Smoking: Current or past smokers face 2 to 3 times higher risk.

- Family history: If a parent or sibling had esophageal cancer, your risk jumps.

- GERD duration: Five years or more of symptoms - even if you’re on meds - is the critical threshold.

Here’s the kicker: having just three of these factors makes Barrett’s esophagus much more likely. And if you’re a white male over 50 with 10 or more years of reflux - even if you only get it once a week - your risk is high enough that screening isn’t optional. It’s essential.

The Red Flags That Mean “See a Doctor Now”

Most people with GERD never develop cancer. But if you start noticing these changes, don’t wait. Don’t assume it’s "just worse reflux." These are the warning signs that cancer may already be developing:

- Dysphagia: Feeling like food gets stuck in your chest or throat. It usually starts with solids - like bread or meat - and slowly moves to liquids. This is the most common symptom at diagnosis, present in 80% of cases.

- Unexplained weight loss: Losing 10 pounds or more in six months without trying. No diet. No exercise. Just weight gone. This happens in 60-70% of advanced cases.

- Heartburn that won’t quit: If you’ve had heartburn more than twice a week for five years or more, that’s not normal. That’s a signal.

- Food impaction: Food literally gets stuck. You feel it. You can’t swallow it. You might even need to vomit to clear it. This occurs in 30-40% of cases.

- Chronic hoarseness or cough: A voice that’s been raspy for more than two weeks, or a cough that won’t go away - especially if it’s worse at night - can be acid irritating your throat and vocal cords.

And here’s what most people miss: new or worsening reflux after age 50, especially if you have three or more of the risk factors above, is a red flag. It’s not aging. It’s a biological shift. The American Cancer Society says 75% of esophageal cancers are found at advanced stages because symptoms were ignored. Don’t be part of that statistic.

What You Can Do to Lower Your Risk

Knowing you’re at risk is only half the battle. The good news? You can cut your risk - significantly - with action.

- Quit smoking: Within 10 years of quitting, your cancer risk drops by half. It’s one of the most powerful moves you can make.

- Manage your weight: Losing just 5-10% of your body weight can reduce GERD symptoms by 40%. That’s not magic. That’s physics - less pressure on your stomach means less acid backup.

- Limit alcohol: Stick to one drink a day if you’re a woman, two if you’re a man. Heavy drinking raises a different type of esophageal cancer, but it’s still dangerous.

- Take PPIs consistently: If you have Barrett’s esophagus, taking proton pump inhibitors daily for five years or more cuts cancer risk by 70%. This isn’t just for heartburn. It’s prevention.

And don’t underestimate screening. Endoscopy - a simple procedure where a camera checks your esophagus - can catch Barrett’s before it turns cancerous. If you’re a white male over 50 with chronic GERD and two other risk factors, current guidelines say you should have one. Yet only 13% of people who qualify actually get screened. That’s a gap. Don’t let it be yours.

What’s Changing in Screening

Screening isn’t stuck in the past. New tools are making it easier, less invasive, and more accurate.

Doctors now use advanced endoscopy techniques like narrow-band imaging and confocal laser endomicroscopy. These let them spot abnormal cells in real time - improving detection by 25-30%. There’s also a new risk calculator called BE MAPPED. It uses seven factors - your age, sex, BMI, smoking, GERD length, family history, and race - to give you a personalized risk score with 85% accuracy.

And the future? Non-invasive tests are coming. The Cytosponge is a pill on a string you swallow. It collects cells from your esophagus as it’s pulled back out. In a 2022 Lancet study, it caught 79.9% of Barrett’s cases. No scope. No sedation. Just a pill and a quick pull. It’s not everywhere yet, but it’s coming fast.

Researchers are also looking at genetics. Some people carry gene variants - like in the CRTC1 gene - that make them 2 to 3 times more likely to progress from GERD to Barrett’s. In the next few years, we may see risk assessment that combines your genes, your lifestyle, and your symptoms into one clear picture.

Why This Matters More Than Ever

Since 1975, esophageal adenocarcinoma has increased by 850%. Why? Because obesity and GERD have exploded. In 1980, 15% of U.S. adults were obese. Today, it’s 42%. More weight means more pressure. More pressure means more acid in the wrong place. More acid over time means more damaged cells. More damaged cells mean more cancer.

And the survival rate? Only 21% for all stages combined. But if it’s caught early - before it spreads - that jumps to 50-60%. That’s the difference between a death sentence and a chance to live. The problem isn’t the cancer itself. It’s the delay. People ignore the symptoms. They think it’s just heartburn. They wait too long.

If you’ve had GERD for five years or more, especially if you’re male, over 50, overweight, or a smoker - don’t wait. Talk to your doctor. Ask about endoscopy. Ask about the BE MAPPED tool. Ask if you qualify for screening. This isn’t about fear. It’s about control. You can’t change your age or your genes. But you can change your habits. And you can ask for the test that could save your life.

Is GERD the same as heartburn?

No. Heartburn is a symptom - a burning feeling in your chest. GERD is the medical diagnosis given when heartburn happens frequently (at least twice a week) and causes damage or complications. Chronic GERD means your esophagus is being exposed to stomach acid regularly, which can lead to Barrett’s esophagus and, eventually, cancer.

Can I get esophageal cancer without having GERD?

Yes, but it’s rare for adenocarcinoma - the most common type linked to GERD. Other types, like squamous cell carcinoma, are tied to smoking, heavy alcohol use, or certain chemicals. But if you’re asking about the type that’s rising fastest, GERD is the main driver. About 90% of adenocarcinoma cases have a history of chronic reflux.

Does taking PPIs mean I’m safe from cancer?

Not completely. PPIs reduce acid and lower your cancer risk by up to 70% if you have Barrett’s esophagus - but only if you take them daily and consistently for five or more years. They don’t reverse existing damage. They slow progression. Screening is still needed if you’re high-risk.

How often should I get an endoscopy if I have Barrett’s esophagus?

If you have non-dysplastic Barrett’s (no precancerous changes), endoscopy every 3-5 years is usually recommended. If low-grade dysplasia is found, you’ll need an endoscopy every 6-12 months. High-grade dysplasia often leads to treatment to remove the abnormal tissue. Always follow your gastroenterologist’s advice - guidelines vary based on your individual risk.

Can losing weight reverse Barrett’s esophagus?

Losing weight won’t reverse Barrett’s esophagus, but it can stop it from getting worse. Studies show that losing 5-10% of body weight reduces GERD symptoms by 40%, which cuts acid exposure. Less acid means less ongoing damage. That’s critical - it lowers your chance of progressing to cancer. Weight loss doesn’t cure it, but it gives your body a chance to stabilize.

What to Do Next

If you’ve had GERD for five or more years - especially if you’re a man over 50, overweight, or a smoker - schedule a conversation with your doctor. Don’t wait for symptoms to get worse. Bring up your risk factors. Ask about endoscopy. Ask about the BE MAPPED tool. Ask if you qualify for screening.

If you’re already diagnosed with Barrett’s esophagus, make sure you’re on a surveillance plan. Take your PPIs daily. Quit smoking. Lose weight if you can. These aren’t optional. They’re your best defense.

Esophageal cancer is not common - but it’s deadly. And it’s preventable, if you act early. Your body gives you signs. You just have to listen before it’s too late.

Jan Hess

Been dealing with heartburn since college and thought it was just stress. Turns out I’m 52, male, overweight, and smoked for 20 years. I just booked my endoscopy. Better late than dead.

Iona Jane

PPIs are just a cover-up. Big Pharma doesn’t want you to know the real cause is glyphosate in your food. They profit off your suffering. Endoscopy? More like a money trap. Your body’s screaming for detox, not a camera up your throat.

Jaspreet Kaur Chana

Man, I read this and thought about my uncle in Delhi - 68, GERD for 15 years, never went to a doctor, drank chai with meals, smoked bidis. Died last year. No one told him. In India, we think burning chest is just spice. But this? This is real. I told my dad to get checked. He’s 65, overweight, drinks two whiskeys a night. He said ‘beta, I’m fine.’ I sent him this article. He’s calling the doctor tomorrow. One person listening can save a life.

Haley Graves

If you’re over 50, male, and have had reflux for five years - stop making excuses. This isn’t a suggestion. It’s a medical emergency waiting to happen. Your doctor isn’t going to chase you down. You have to be the one to ask. Endoscopy takes 15 minutes. Cancer takes years to kill you. Choose now.

Diane Hendriks

The notion that ‘GERD causes adenocarcinoma’ is a reductionist fallacy. The data correlates, yes - but causation requires controlled longitudinal studies accounting for confounding variables like dietary acrylamide, gut microbiome dysbiosis, and epigenetic methylation patterns. To reduce this complex pathophysiology to ‘lose weight and take PPIs’ is not only medically irresponsible - it’s a disservice to public health literacy.

ellen adamina

I had silent reflux for years. No heartburn. Just a cough that wouldn’t quit. I thought it was allergies. Turns out it was acid eating away at my throat. Got screened. Had Barrett’s. Now I’m on PPIs, lost 18 pounds, and quit smoking. I’m alive because I listened. Don’t wait for the food to get stuck.

Tom Doan

So let me get this straight. We’re being told that if you’re a white male over 50 with a belly, smoke, and have had heartburn since the Clinton administration - you’re basically a walking cancer incubator. And the solution? Pay $2,000 for an endoscopy that might not even change anything. Meanwhile, the real problem - corporate food, sedentary jobs, and profit-driven medicine - remains untouched. How convenient.

Annie Choi

Just had my first Cytosponge test last week. Pill on a string? Yeah. Swallowed it. Felt weird. Pulled it out. No sedation. No nausea. Got my results in 10 days - no Barrett’s. Best $300 I ever spent. If you’re high-risk, don’t wait for the scope. Ask for the sponge. It’s the future. And honestly? Less terrifying than a colonoscopy.

Ayush Pareek

My father passed from this cancer. He ignored it for years. Said ‘it’s just indigestion.’ I’m 34, got tested last year - no Barrett’s, but I quit smoking, lost weight, and take PPIs anyway. I don’t want my kids to lose me like I lost him. This isn’t fear. It’s responsibility. If you’re reading this and you’re at risk - do it. For them. For you.